Libraries have always been a reflection of the transformations and conflicts that societies experience, as well as of cultural exchanges and openness to others, regardless of background or belief. Everything happening in the outside world, from cultural movements and the questions being raised, to debates and literary works, echoes within these open spaces.

The shelves of libraries showcase the ideas humanity has produced across the ages, spanning diverse fields from jurisprudence and philosophy to literature, medicine, engineering and beyond. Libraries are the one place where we can truly witness the journey of ideas and engage with them directly. The books they house have passed through many stages: from a mere idea to a manuscript, to a compiled work and finally to a printed book.

Since ancient times—Sumerian, Akkadian and Greek—libraries and centers of knowledge have been closely linked with places of worship and royal palaces. These spiritual and political spaces were driven by the desire to acquire knowledge, pursue science and promote advancement for both individuals and societies. The same was true in various Islamic regions, particularly as states formed and opened up to neighboring civilizations. From the Levant, Baghdad, Egypt and Kairouan to Morocco and Al-Andalus, mosques served as the foundational hub around which Qur’anic schools and libraries grew. Nearby, within the bustling markets, scribes, copyists and all those connected to the craft—whether directly or indirectly—were widely present.

Books in the hands of the public and the elite, HC.HP.2016.0089-0106

Beginnings are often difficult to define in terms of time and place. They are a domain of conjecture, speculation, interpretation and conflicting narratives. Questions like, “When did it begin? From where and with whom?” not only lack definitive answers but are themselves misleading and fragmented inquiries. Primary sources do little to assist us in tracing the early development of books and libraries, and when they do exist, they are often insufficient and inconclusive.

Through this blog post, our journey takes us from Qatar National Library to the ancient libraries of Morocco. It is a journey across great distances and time—from a far flung past shrouded in mystery and secrets, to a present and future that embrace innovation, advanced technologies and intertwined knowledge pathways.

Our exploration of Moroccan libraries will investigate the treasures of the Hassania Library in Rabat, browsing its rare manuscripts and printed works. From there, we are forced to cross the Mediterranean sea to Spain, tracing the journey of the Zaydani Library—also known as the Escorial Library—which was seized off the Moroccan coast and rerouted in an act of piracy in the early 17th century. Its manuscripts eventually ended up in far-off palaces and monasteries, hidden away from their original readers. They remained there, out of reach, held captive for centuries.

It is remarkably strange that time—so often relentless in erasing treasures—has preserved the manuscripts and books of this collection. In tracing the fate of this library, we recognize that the destiny of a book or manuscript can sometimes mirror that of its author or collector. It may face exile, displacement and neglect, enduring sorrow and estrangement from its homeland.

In Morocco and throughout the Islamic world, the collecting of books, the building of libraries, and the pursuit of knowledge were never passing trends tied to isolated events. Rather, they were enduring traditions—almost devotional pursuits—rooted in a grand civilizational mission embraced by Islamic states. Every Muslim was not only expected to understand and spread the Qur'anic message but to embody and practice its teachings.

Thus emerged a continuous movement of collecting, transmitting, simplifying, explaining, interpreting, translating and commenting—an intellectual current that never rested. One text supported another, one book enriched or challenged its predecessor. Multiple copies of a single title circulated and scribes spread across shops and public squares. Paper merchants thrived, and books and calligraphy assumed a central place in the life of all Muslims, who were deeply engaged with religious questions and the complexities—both spoken and unspoken—of everyday life.

Yet Muslims were never detached from the practicalities of their existence—they were merchants, sailors, physicians, travelers and warriors. The book remained a constant companion, whether at home, in the mosque, in spiritual lodges or in military outposts. It was also a source of comfort in the solitude of deserts and during long journeys.

The history of Morocco’s book collections is rich and multifaceted, filled with wonders, legacies and age-old traditions as ancient as the land and its people. Libraries were established with purpose and vision—by scholars in their homes and by rulers in their palaces—while mosques and schools benefited from their collections through gifts, endowments, loans or bequests.

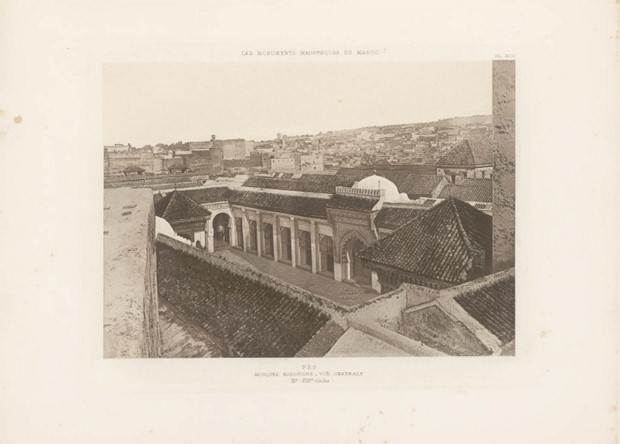

With the rise of the Idrisid state at the end of the 2nd century AH/8th century CE, Morocco witnessed the birth of its first Islamic city, Fez. It became a center of settlement for Andalusians and people from Kairouan. Two grand mosques were established—the Qarawiyyin Mosque and the Andalusian Mosque. There, state officials and scholars worked hand in hand to build libraries within palaces and courts where intellectual gatherings and debates were held, inspired by the Abbasids in Baghdad and the Umayyads in Córdoba. Kings recruited scribes to copy books and enrich collections in various sciences, making them accessible to scholars and literary figures.

A general view of Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fez at the end of the 19th Century: a place of devotion and a center for the transmission of knowledge. HC.FB.03440

Despite the political instability and decline that followed the fall of the Idrisids, this intellectual momentum never waned. It was revived under the Almoravids in the late 5th and early 6th centuries AH/11th and 12th centuries CE. Libraries flourished across Moroccan cities, with Marrakesh emerging as a leading capital. Scholars and writers flocked to its intellectual gatherings, and prized books and manuscripts were imported from Andalusia. Kings and nobles competed to acquire rare books and ancient texts to enrich their libraries, particularly as the influence of Maliki scholars grew during their rule.

Private libraries owned by scholars, judges and high-ranking individuals, along with libraries attached to royal courts and palaces, equally played a significant role in advancing knowledge. Arabic sources abound with descriptions highlighting the deep passion these figures had for books and libraries. In biographical works such as “Al-Dhayl wa Al-Takmila” (The Supplement and Continuation), by Andalusian scholar Abu Abdullah al-Marrakushi, they were often portrayed as ardent book collectors, chroniclers of history and connoisseurs of rare manuscripts penned in the hands of eminent masters. Some accounts even mention scholars who transported collections of books with them on pilgrimage to Makkah or as they relocated to new places of residence.

Likewise, public libraries attached to schools and religious lodges played a major role in promoting access to, and the circulation of, books. Contrary to modern assumptions, however, these libraries were not open to the general public. Rather, they catered to a specific audience, primarily students and specialists in religious and scholarly disciplines.

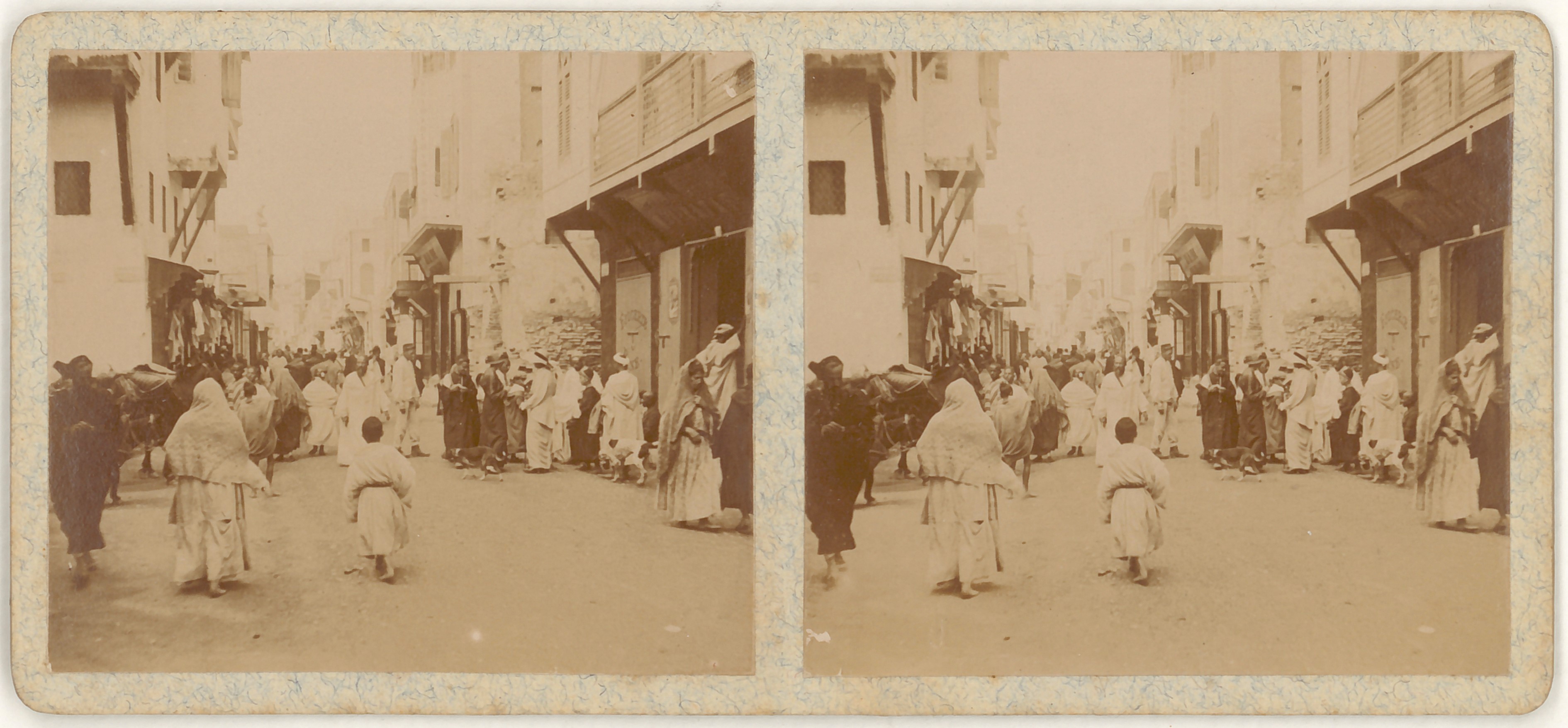

Although many surviving manuscripts from this early period were written on parchment, the development of paper production marked a major turning point. According to historian Muhammad Al-Mununi in his book “Tārīkh al-Warāqa al-Maghribiyya” (History of Moroccan Bookmaking), the city of Fez alone boasted as many as 104 paper mills, particularly concentrated in the Bab Al-Hamra district. This advancement significantly supported the flourishing of manuscript culture in the region.

The vibrant markets and alleys of Fez, Gaston Jules Louis Durel (d.1954), HC.HP.2020.0041.

Paper production flourished and deepened across provinces and regions with the rise of the Almohads to power in the second half of the 6th century AH/12th century CE. This was driven by the growth of the professions of manuscript copying and bookmaking, the spread of authorship and the increasing competition among craftsmen to perfect their work. Writers began to prefer paper produced in the city of Ceuta, as it was considered of higher quality than that of the Andalusian city of Xàtiva.

The caliphs paid special attention to their book treasuries. Overseeing them was considered a prestigious and honorable position, reserved only for the elite and the most learned among them.

At an accelerated pace and with growing interest, libraries in Morocco – under the Marinids, Saadians, and later the Alaouites – underwent significant developments, building on the rich heritage accumulated over generations and dynasties. By the second half of the 19th century, Moroccan libraries witnessed a transition from a manuscript culture to one shaped by the advent of printing, marking the beginning of a new phase in the relationship with the written word.

Preserving this Moroccan and human heritage was not an easy task, as libraries were never immune to crises and disasters. They were threatened by many forces: human, animal, natural, and political. From insects and rodents, to damp and floods, to civil strife, war, looting and theft—libraries faced severe dangers.

Yet, books proved remarkably resilient, enduring many of these calamities. Though many were lost, a portion withstood the test of time. The fate of the Escorial Library in Spain is a powerful example of such resilience.

Like other libraries around the world, Moroccan libraries also suffered setbacks and crises due to sectarian and ideological affiliations. Some caliphs and rulers resorted to burning many books of philosophy, considering them sources of sedition, heresy and foreign ideas incompatible with religion. The persecution of the philosopher Ibn Rushd (also known as Averroes), and the burning of his books and those of his followers at the hands of the Almohads, is a case that has been passed down through generations.

Despite all these challenges and catastrophes, books remain the conscience of humanity and a witness to its civilization. Human life before writing, documentation and the production of texts was often open to interpretation, illusion or even myth. In Arab-Islamic civilization, books have been a cornerstone of intellectual construction, communication, historical record and the pursuit of truth.

Today, we face profound and fateful challenges concerning the future of books, manuscripts and the evolution of libraries. Will we reach the point some have predicted—where libraries cease to exist? Or will we align ourselves with those who defend books and their continued relevance, as the American historian Robert Darnton argues in his work The Case for Books: Past, Present, and Future?

As we await what the near future will bring, there are truths that must be acknowledged. Digital libraries are now competing with the physical book and displacing it from the shelves, engaging in a battle it did not choose. Will paper as a medium for writing survive the overwhelming tide of screens, technology and artificial intelligence?

In our current time, rethinking the future of libraries—by revisiting these ancient repositories—has become an urgent need. This is essential for envisioning a future for upcoming generations, so that libraries are not abandoned or reduced to museum institutions preserving the collective past, classifying it by eras and civilizations, or becoming merely places for leisure and sightseeing.

Add new comment